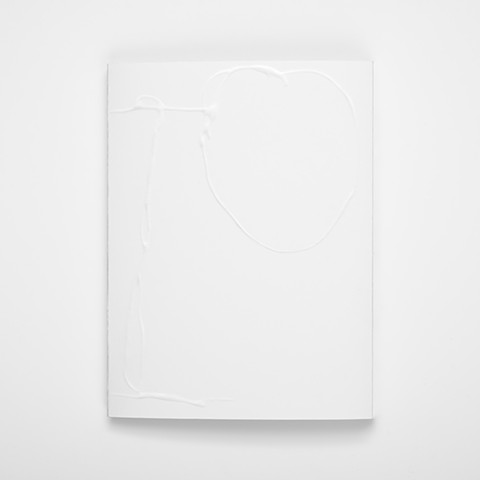

Collapse

If the mind is a muscle, consciousness cannot be known unto itself, but can only be demonstrated and shared via gesture.

Catherine Wood, The Mind is a Muscle

All other mediums are rendered irrelevant when one’s body is allowed to be its catalyst for expression. Since the advent of Abstraction, the body’s place within painting has been fraught. In some instances its representation has been denied almost entirely for the sake of a more pure Modernist visual literacy. Surface, color, and geometry vs. skin, meat, and bone. The body never should have been accepted as mere subject that could simply be displaced, peeled apart, ignored, or splattered from edge to edge in the hopes that that finally did the trick of eliminating figure vs. ground, consciousness vs. nature, expression vs. restraint. The figure only truly meets its ground in sleep, sickness, or death. All of which have, at best, a tenuous relationship with consciousness. So, we have learned to survive through abstraction, couched in an eternal suspension, albeit an illusion, beyond the binary. Abstraction has become our core method for personalizing meaning in all communication and everyday experiences. It welcomes subjectivity, allowing one to find intimacy in politics, privacy in symbols, and one’s reflection in the everyday. However, one rarely remains abstract and understood, especially today as our meaning remains radically contingent on so many broken systems. So we perform in the hopes that it’s enough to ward off the inevitable infection of doubt and breakdown. We have become the subjects of an incomprehensible amount of skepticism in the systems that have prevailed. We strive for the freedom that abstraction affords us in meaning-making, but in the service of a cancerous pluralism: yours, mine, theirs, ours are all just fine as long as we can still breathe. For one to enjoy the private pleasures of the abstract one must not contend with the realities of the body and all of its limitations, this we share.

Collapse puts Yvonne Rainer’s tuck / roll and Philip Guston’s digging gaze, both circa 1966, in conversation, as a shared moment of breakdown. It is the breakdown of a medium and a gesture. Though Rainer and Guston deploy vastly different techniques and mediums, both engage the breakdown of intentions to move beyond the limits of inherited languages and traditions. The return to rudimentary marks and a balling up of one’s self through a moment of pause signifies a deep, mutual vulnerability in the service of change.

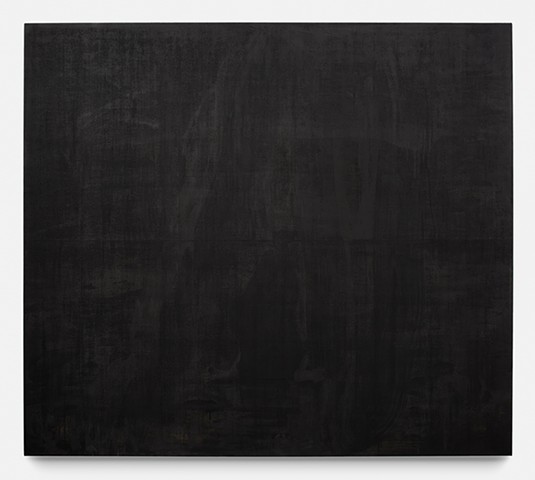

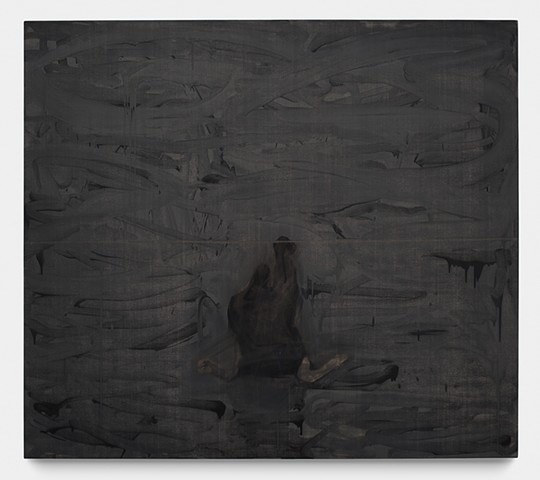

Philip Guston is one of a handful of painters to straddle the gaping hole between Abstraction and Representation. Around 1965 Philip Guston reverted to looking inward, abandoning his fleshy color palette and enlisting ink drawing and black scribbled shapes to dissect his motives and begin anew. He continued to dismantle his practice and break it down to its bare essentials: line and form. This process was part of a deep psychological restructuring of his practice, which, he realized, could no longer capitalize on an identity tied to Abstract Expressionism. The break was never a clear moment but rather an ongoing dilemma that surfaces in awkward, questionable gestures and clichéd desires to ‘return’ to what was, to see painting as though it had never existed, and to hope that starting over was even still an option. At stake were the ethics of representation in painting. In works like Air II and Position I, both from 1965, black strokes meander into a head shape floating within a field of interwoven grey gestures. All of which precede the second and more publicly criticized phase of his career, with the self and its fragmented body stuck in time.

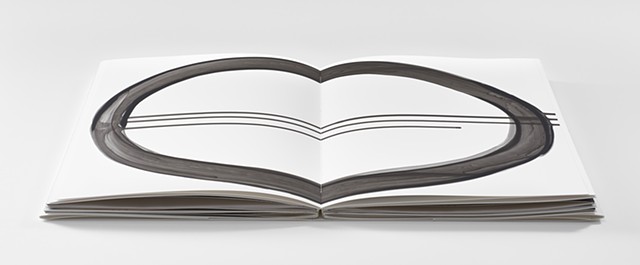

During her recorded performance of “Trio A” (originally performed in 1966), Yvonne Rainer continuously looks outward at the space surrounding her and the audience. This outward gaze questions the spectacle of performance, and demonstrates a hesitation to be looked at / seen as an object of entertainment. But 2 minutes and 49 seconds into her performance, Rainer breaks her gaze when she rolls backwards. With her eyes and nose buried into her stomach and her hands hovering in mid-air, her body blocks her outward gaze as her legs fold over her torso. Her posture is awkward and, as it submits to the backwards tumble, necessarily vulnerable. These two seconds may seem rather innocuous, but pausing the recorded footage at these intervals and meditating on the position of such a performer (where she quickly becomes re-entrenched in the spectacle of the gaze) allows us to witness powers (i.e. political, social, and discursive) that never fail to penetrate one’s gestures and critiques. The outside always gets in.

Today, Yvonne Rainer’s claim to “seeing difficulties” has never had a more significant resonance. The difficulty in seeing has become multi-faceted, atemporal, and is uniquely now our shared blind-spot. From Rainer’s class oriented and ‘task-like’ gestures to Guston’s hooded heads and chopped limbs, we are witness to an ongoing and exhausting recognition of the same sociopolitical paradigm. We have become lost in a fog of Abstraction.